On the morning of March 2, 1915, a catastrophic explosion tore through the No. 3 Mine in Layland, West Virginia, operated by the New River & Pocahontas Consolidated Coal Company. It was the second mine explosion in a month in Fayette County, and one of the deadliest mining disasters in its history, killing nearly 200 miners and leaving the town reeling in shock.

What made this disaster all the more devastating was that the No. 3 Mine was considered the safest in the region. Inspectors had cleared it of gas and coal dust hazards yet the explosion ripped through two miles of underground tunnels, unleashing destruction felt 10 miles away.

At 8:30 a.m., the ground trembled as the explosion roared through the mine. Heavy masonry at the entrance was blown apart, and debris choked the mine’s opening. Above ground, houses were damaged, windows shattered, and a house’s roof was lifted off its frame.

A railroad porter, Ab Cooper, and his dog were standing 75 yards from the mine mouth when the blast erupted. The force hurled him into a telephone pole, snapping the 8-inch chestnut wood in half. He survived the initial impact but succumbed to his injuries within the hour—becoming the only fatality outside the mine.

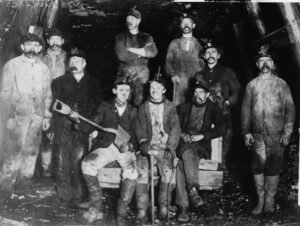

Inside, however, the situation was even worse. Nearly 200 men were working underground, most of them immigrant workers from Italy and Russia, as well as local farm laborers from Springdale, Backus, and Crickmer. In the immediate aftermath, there was little hope for survival.

Rescuers entered the mine at 11:00 A.M., led by Superintendents Clapperton and Kneer, Mine Boss Nahodel, and experienced miners. They encountered heavy smoke, scattered debris, and collapsed stoppings, but no immediate signs of life.

Astonishingly, six men emerged alive, among them “Big Jack” Koxelfsky, who was carrying a stunned Benny McDaniel to safety. These were the only known survivors in the initial hours.

As the rescue teams pushed deeper, they found four bodies by Wednesday noon, but conditions were still too dangerous for further searches. The heat inside the mine was overwhelming, and Deputy Inspector Holliday was overcome by fumes, needing to be carried out. Smoke and soot coated everything, complicating recovery efforts.

By Saturday morning, when rescuers cleared the mine’s entrance, five miners unexpectedly walked out alive. Trapped in the ninth left entry, they had survived for days but were finally able to escape when air quality improved. Their story, however, held a shocking revelation—they had found a note indicating that 41 more men were alive, sealed off behind a slate barricade in the tenth left heading.

Rescue teams rushed inside and discovered all 41 men alive, though they were weak and starving. They had spent four days in darkness, chewing shoelaces and mine timber bark to fight off hunger. Many had prayed for rescue or a swift death to end their suffering. Their survival was nothing short of miraculous.

The Layland Mine was not supposed to explode. Inspectors—including John Absalom and Robert Muir—had thoroughly examined it just days before, and no gas or excessive dust was found.

Yet, the explosion was undeniably fueled by coal dust, which had settled in the tunnels and was easily ignited. Investigators later found evidence of a misfired dynamite shot that likely triggered the blast. The small barrier of coal near the explosion site was too weak to contain the force, allowing fire and pressure to spread rapidly through the mine.

Theories included:

• A hidden pocket of gas released by a fall of slate

• A blown-out dynamite shot that stirred up explosive dust

• The presence of fine coal dust accumulating in unseen areas

Whatever the cause, the Layland Mine disaster left experts dumbfounded. As Deputy Inspector Absalom put it, “Of the 95 mines in my charge, this is the last one I would ever look to see an explosion in.”

Layland, once considered a safe haven for miners, became the site of one of the deadliest coal mining disasters in West Virginia history. In the days that followed, rescue teams recovered bodies, and hundreds gathered outside the mine, awaiting news of loved ones. A makeshift morgue was set up and 75 coffins were brought in by train, with more to follow.

The Layland Mine Disaster was a loss for an entire community. Families lost fathers, brothers, and sons in an instant, and the so-called safest mine became its deadliest. Today, it stands as a grim reminder of the dangers of coal mining, even in the best conditions.

When I was a child I lived not to far from this mine at Lawton WV. We drove past it everyday and was reminded of the coal mine disaster that took so many lives! Very sad.